Ogmios- Ogme-Smertrios- Héraclès

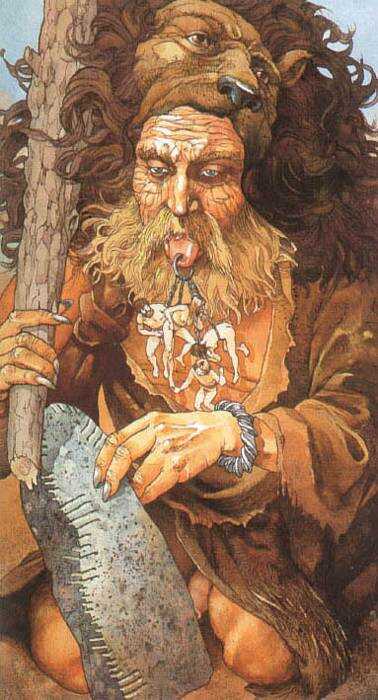

Ogmios est représenté âgé, vêtu d'une peau de bête et porteur d'une massue

Épigraphiquement, Ogmios s’il est incontestablement attesté n’est cependant pas fréquemment représenté. En provence il apparaitra sur une inscription à Castellane dans les Alpes de Haute Provence où il est invoqué comme Hercule-Ogmios . Comme Ogmius (la forme latinisée de son nom), il est connu par une inscription trouvée à Reims. Cependant les plus célèbres inscriptions relatives à cette divinité proviennent de deux defixiones (comprimés de malédiction) trouvées à la source à Bregenz sur le lac de Constance en Autriche, où Ogmios est invoquée avec Dis Pater le père des Celtes et où on lui demande d'intervenir et de jeter une malédiction sur une femme stérile de sorte qu’elle ne trouve jamais de mari. Ce lien entre Defixio et Ogmios n’est pas incongru si on songe qu’il est, selon Lucien de Samosate, une divinité métaphoriquement contraignante à même d’enchainer les hommes par le pouvoir de son éloquence.

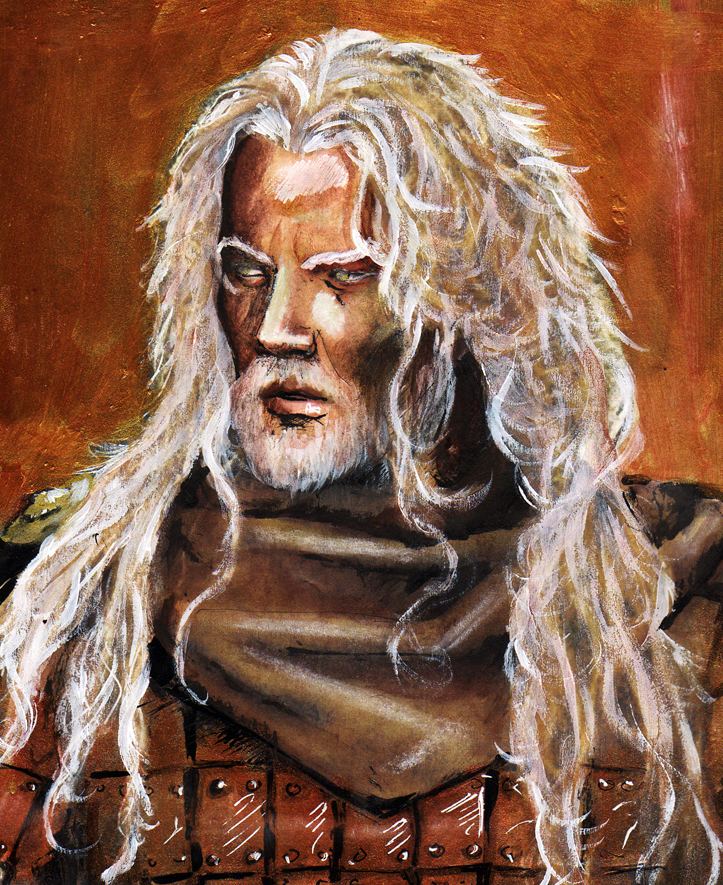

En effet, Ogmios en Gaule et Ogme en Irlande est le champion des Túatha Dé Dánann irlandais. C'est le dieu des liens, homologue au dieu védique Varuna. A l’instar d’Héraclès, Ogmios est considéré lui aussi comme un champion, mais Ogme est de surcroit un Dieu psychopompe qui chapeaute les morts. C'est à lui que les Celtes vouent les armes de l'ennemi vaincu ; celles-ci étant soit abandonnées en monceaux sur les champs de batailles, soit détruites lors de rituels dans des sanctuaires. Ogmios/Ogme est la partie sombre de la grande Divinité Souveraine, contrairement au Dagda qui lui représente la partie claire. L'Irlande lui attribue l'invention de l'écriture magique, les Oghams. Il ne fait pas la guerre, même s'il en est le dieu. En revanche, il la commande et la surveille

Un autre avatar herculéen fréquent en Gaule est Smertrios, dont le nom est connu par le Pilier des Nautes trouvé sous Notre Dame de Paris en territoire Parisii. Il est étymologiquement celui « Celui qui prévoit », le « Providentiel », le « Pourvoyeur », « Celui qui supprime les difficultés de la vie ». On retrouve d’ailleurs cette même racine dans le nom de sa parèdre féminine Rosmerta représentée portant une corbeille de fruits, une patère, une bourse ou une corne d'abondance. Là encore une cohérence avec les vertus civilisatrices attribuées à Héraclès.

« Dans les quelques bribes christianisées des anciennes croyances païennes concernant Oghma qui nous ont été enregistrées dans la littérature médiévale irlandaise, ce dernier est considéré comme une des principales divinités célestes irlandaises Tuatha Dé Danann, et sa personnalité est définie par un certain nombre de traits singuliers :

-

Il est un maître de la parole sacrée, qu’elle soit exprimée oralement (il est reconnu « savant en éloquence et en poésie ») ou par écrit puisqu’on lui attribue l’invention des Oghams, un système d’écriture alphabétique à vocation magique qui porte son nom, apparu en Celtique insulaire au Bas Empire et inspiré de l’alphabet latin, et qui selon toute vraisemblance était une forme modernisée de l’ancienne technique divinatoire et incantatoire par les « bois de sort » attestée déjà chez les gaulois(Pline l’ancien HN, XXV,105)

-

Il est un Dieu lieur capable d’enchaîner à lui les individus

-

Il est le violent champion du roi des Tuatha Dé Danann disposant d’une force guerrière sans équivalence qui en fait le champion des champions

-

Il est le gardien potentiel de la pierre de Fàl, un des quatre talismans se souveraineté irlandaise qui désignant par un cri tout nouveau « ard ri Erenn » haut roi d’Irlande

Cette personnalité qui mêle la compétence druidique et celles guerrière au plus haut grade, et qui le crédite d’un rôle de garant et de protecteur du pouvoir royal, peuvent sembler hétérogènes de prime abord mais constituent en réalité un ensemble organique des plus cohérents : une telle codification fonctionnelle répondent en effet au modèle du Dieu incarnant le souveraineté magico-guerrière de la théologie indo-européenne que Georges DUMEZIL a jadis mis en évidence à partir de l’exemple du Dieu védique Varuna, roi primordial de l’univers incarnant le ciel nocturne… Les personnalités de l’Héraclès-Ogmios gaulois et de l’Oghma goïdélique se recoupent sur deus domaines de prédilection que sont l’éloquence et la valeur militaire et manifeste les l’unité existant entre les théologies celtique continentale et insulaire à propos d’Ogmios/Oghma. Les textes mythologiques et épiques irlandais éclairent encore un autre aspect fondamental du Dieu Oghma : son activité lithobole , c'est-à-dire de lanceur de pierres »

Valery RAYDON

Ogmios is perhaps amongst the most well-known of the Celtic gods and yet, in truth, he is a deity about whose existence very little is known and even less is documented. One of the main reasons that he is known is because he was written about by the Greek rhetorician and satirist Lucian of Samosata who relates a discussion he had with a Celt regarding the demi-god Herakles (Hercules): The Celts call Heracles Ogmios in their native tongue, and they portray the god in a very peculiar way. To their notion, he is extremely old, bald-headed, except for a few lingering hairs which are quite grey, his skin is wrinkled, and he is burned as black as can be, like an old sea-dog. You would think him a Charon or a sub-Tartarean Iapetus — anything but Heracles! Yet, in spite of his looks, he has the equipment of Heracles: he is dressed in the lion's skin, has the club in his right hand, carries the quiver at his side, displays the bent bow in his left, and is Heracles from head to heel as far as that goes. I thought, therefore, that the Celts had committed this offence against the good-looks of Heracles to spite the Greek gods, and that they were punishing by means of the picture for having once visited their country on a cattle-lifting foray, at the time when he raided most of the western nations in his quest of the herds of Geryon. But I have not yet mentioned the most surprising thing in the picture. That old Heracles of theirs drags after him a great crowd of men who are all tethered by the ears! His leashes are delicate chains fashioned of gold and amber, resembling the prettiest of necklaces. Yet, though led by bonds so weak, the men do not think of escaping, as they easily could, and they do not pull back at all or brace their feet and lean in the opposite direction to that in which he is leading them. In fact, they follow cheerfully and joyously, applauding their leader and all pressing him close and keeping the leashes slack in their desire to overtake him; apparently they would be offended if they were let loose! But let me tell you without delay what seemed to me the strangest thing of all. Since the painter had no place to which he could attach the ends of the chains, as the god's right hand already held the club and his left the bow, he pierced the tip of his tongue and represented him drawing the men by that means! Moreover, he has his face turned toward his captives, and is smiling.

I had stood for a long time, looking, wondering, puzzling and fuming, when a Celt at my elbow, not unversed in Greek lore, as he showed by his excellent use of our language, and who had, apparently, studied local traditions, said: "I will read you the riddle of the picture, stranger, as you seem to be very much disturbed by it. We Celts do not agree with you Greeks in thinking that Hermes is Eloquence: we identify Heracles with it, because he is far more powerful than Hermes. And don't be surprised that he is represented as an old man, for eloquence and eloquence alone is wont to show its full vigour in old age, if your poets are right in saying 'A young man hath a wandering wit' and 'Old age has wiser words to say than youth.' That is why your Nestor's tongue distills honey, and why the Trojan counsellors have a voice like flowers (the flowers mentioned are lilies, if my memory serves). This being so, if old Heracles here drags men after him who are tethered by the ears to his tongue, don't be surprised at that, either: you know the kinship between ears and tongue.

This is obviously a very vivid account, but how much stock can we truly put into it? After all Lucian was a satirist... Was he using the notional 'Celt' to belittle the figure of Hercules? Of course he could have been recording events faithfully but was recording a misapprehension. Lucian pointing to a statue of Hercules and the Celt responding with an analogy peculiar to his own people and tribe. To reach the truth we need to examine the statement above in the context of all extant evidence concerning the god Ogmios. We have the image from coins originating in northern Gaul (above left) which seem to show a central figure whose lips/tongue are joined to three smaller heads surrounding the main figure. This could be a depiction of Ogmios. Equally it could relate to the Celtic 'cult of the head'. Then again, it could equally relate to both. The evidence in this case must remain inconclusive.

Epigraphically Ogmios is almost as elusive. He is known from an inscription at Castellane, Alpes de Haute Provence, France where he is invoked as Hercules Ogmios. As Ogmius (the Latinized form of his name) he is known from an inscription found at Reims, France. However, the most famous inscription to this deity come from two lead defixiones (curse tablets) fount at Bregenz, Lake Constance, Austria where Ogmios is invoked along with Dis Pater and Ogmios is requested to intervene and lay a curse on a barren woman so that she would never marry:

The epigraphic evidence is thus scant, though it does indicate that a deity known as Ogmios was worshipped in north-eastern Gaul and this deity, at least in one instance, was equated by interpretato Romana with the Greco-Roman demigod, Hercules. There is also the potsherd found at Richborough that bears the name 'Ogmia' and depicts a figure with long curly hair and solar rays emanating from his head. Which leaves us with iconographic evidence. The image of 'Hercules' is well known in the Classical world. As described in the Lucan passage above, Hercules is the one who carries 'the club in his right hand, carries the quiver at his side, displays the bent bow in his left'. The image of 'Hercules' with club in hand occurs all over the Romano-Celtic world. A good example being the carving from Aix-en-Provence, France (shown above right) another more 'classical' example comes from High Rochester (Bremenium), Northumberland which depicts Hercules with club, bow and quiver. All these images, however, only occur after the Roman conquest so they do not speak directly to there being a native deity of this type. Indeed, even the most famous 'Hercules' depiction, that of the Cerne Abbas giant (above left) in now thought to be Romano-British rather than iron age in origin. It does seem likely though that the prevalence of such imagery in Romano-Celtic times echoed something that existed within the Celtic cosmogony, a deific principal the became syncretized with Roman Hercules and for the sake of convenience we can call this principle 'Ogmios'. What then of the deity himself? The only evidence (apart from Lucian) we have for this deity comes from Irish sources where there is an equivalent deity, Ogma.

Ogma, sometimes known as Ogma Grianainech (of the sun-like countenance), and Ogma Milbél (honey-mouth). In the Irish legends Ogma is the the son of the Fomorian king, Elatha and is the brother of the Dagda. The name of Ogma's mother is uncertain, though she is generally considered to be Brigid. He is considered as one of the Tuatha Dé Dannan's three principal champions (along with Lugh Lámfhota and the Dagda). This is why, at Lugh Lámfhota's request for admittance into the Tuatha Dé court Ogmios challenges him to a challenge of strength involving the throwing of a flagstone (Ogmios loses). He is also considered the divine patron of poetry and eloquence, which explains his epithet of Milbél. In this respect Ogma is also considered to be the inventor of the Ogham alphabet, a system of writing based on the Latin alphabet but composed of strokes and notches cut upon the edge of a piece of wood or stone. As a writing form it is attested in Ireland and western Britain from about the fourth century CE, though it may represent the extension and continuation of an older mnemonic system. Though the name of the alphabet is the philological cognate of Ogma's name it could be that they are derived from the same root word or even that Ogma's name is derived from that of the alphabet.

It is interesting to note that the relationships between the Irish deities Ogma, In Dagda and Brigid are echoed by the possible relationships between Ogmios and Dis Pater as mentioned in the Bregenz defixione. Also, Bregenz is itself named after the goddess Brigantia, cognate of Brigid. In Gaul therefore we have an echo, or at least a hint, of a similar relationship existing between the Gaulish trilogy and their Irish cognates. This might lend support to one theory that the name of Irish Ogma is actually derived by learned borrowing of from Ogmios possibly via Lucian. In a broader context Lucian's description of Ogmios would indicate that he was somehow a 'binding' deity, metaphorically and literally chaining his victims with the eloquence of his words. This 'binding' aspect of Ogmios' nature also explains why he was invoked on the Bregenz defixione to bind with a curse. The nature of his use of words to bind may well relate to an older function of this deity as a psychopomp where he led the souls of the departed from this world to the next; which makes considerable sense in terms of Celtic culture. For one of the functions of the poet was to glorify his lord and his battles. In death the poet would also sing his lord's eulogy.

No satisfactory meaning for Ogmios' name has, as yet been made and attempts to interpret the name using the reconstructed proto-Celtic lexicon are speculative at best (mostly attempting to use Ogmios' perceived attributes to derive an interpretation to do with 'strength' and 'furrowing'). It may be that the name is derived from an unknown root to do with 'language', 'knowledge gained through language', 'the binding power of language' but this, again is simply speculation as there is no direct linguistic cognate in any of the extant Celtic language

A découvrir aussi

Retour aux articles de la catégorie Panthèon -

⨯

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 25 autres membres