Panthèon

Inanna, Monde d’en Bas et Mariage Sacré

Article de Patricia Buigné-Verron www.mouvement-interieur.org

Inanna est une déesse sumérienne dont on a retrouvé trace sur des tablettes d’argile gravées en écriture cunéiforme. Les deux extraits ci-dessous sont une « adaptation libre » de sa mythologie. Ils constituent deux passages d’un texte plus complet qui souhaite explorer, à travers diverses mythologies, un Féminin authentique oublié.

Descente dans le Monde d’en Bas

Je descends dans l’obscurité de l’humanité…

Je dois passer sept portes, toutes gardées par un portier

Qui veille à ce que la règle antique soit respectée.

A chaque porte, je dois décliner mon identité :

« Je suis Inanna, de là où le Soleil se lève ! »

Mais dans ce pays d’ombre, le portier n’en n’a cure,

Et chaque fois, il me demande de me défaire d’une de mes parures.

Je m’incline et lui laisse successivement ma couronne, mes bijoux de front, mon module de lazulite,

Mon collier, mes perles-couplées, mes bracelets, mon cache-seins et mon manteau royal…

Et pendant tout ce temps, inexorablement, je descends… je descends…

Je suis le grain qui meurt et je suis la terre qui enfouit le grain.

Tandis que le portier me déshabille de mes enveloppes,

Au cœur du grain, le germe se développe.

Et, si progressivement j’agonise,

Assurément je me végétalise.

Dépositaires de mes rituels, vos évangiles disent :

« Si le grain de blé qui est tombé en terre ne meurt, il reste seul ;

Mais, s’il meurt, il porte beaucoup de fruits »

Et toujours, je descends… Je descends…

Mes sept étapes sont mon chemin de joie.

Chacune d’elle me plonge dans l’émoi

Tandis que se dissout tranquillement mon « moi ».

Ma descente devient danse décente

Où je dévoile ma pudique nudité

Tout en jouant avec mes voiles :

Voilée… dévoilée…

Je suis celle que vous voulez… Je suis celle que je suis…

Je suis celle que vous voilez… Je suis celle que voilà…

Et ma danse des sept voiles me fait voyager dans sept niveaux de conscience,

Sept planètes, sept couleurs ou sept chakras, comme vous voilez…

Où chaque fois, je laisse une vieille identité pour mettre à nu ma vérité.

Et encore, je descends… Je descends…

Progressivement, je me rêve-Elle.

Qui ça Elle ? Ma sœur peut-être,

Ou bien encore… la matière originelle, celle dont est faite la matrice profonde.

Celle où beauté et laideur extrêmes s’unissent et se confondent.

Celle où fécondité et pourrissement, harmonieusement mêlés,

Constituent ensemble un processus sacré.

Celle où deux sœurs, de Lumière et d’Ombre

Se trouvent être deux faces d’une même entité.

Ma descente est terminée.

Me voici arrivée.

Dans le Royaume des morts, Ereshkigal m’attend depuis longtemps.

Nue, face à elle, dans le noir regard ma sœur d’En-Bas,

C’est moi-même exilée que je vois dévoilée.

En un instant, dans le miroir de ma profondeur mystérieuse,

Je me réapproprie la part ténébreuse

Que l’on m’avait ravie.

La déesse fragmentée,

Adaptée aux normes collectives,

Refoulant dans l’ombre sa force instinctive primitive,

Retrouve soudain son entièreté.

Sauvée des âges, je redeviens la déesse sauvage.

Alors, autour de moi, tout se met à danser :

Il n’y a plus ni Inanna, ni Ereshkigal,

Ni haut, ni bas, ni vie, ni mort, ni cosmos, ni chaos,

Ni masculin, ni féminin, ni blanc, ni noir, ni passé, ni futur…

Il n’y a que l’Instant Présent,

l’Aventure de la Nature et son Grand Cycle des transformations.

Et donc, je me soumets.

J’entends les Sept Juges du monde d’En-Bas m’annoncer leur sentence,

Et je sens le regard de ma sœur pénétrer ma substance.

Il me lit et me lie tandis que son cri me détruit.

Je suis le grain qui meurt avant d’être plus tard l’épi.

La brillante Ereshkigal prit alors place sur son trône

Et les Anunna, les Sept Juges, articulèrent devant elle leur sentence !

Elle porta sur Inanna un regard : un regard meurtrier !

Elle prononça contre elle une parole : une parole furibonde !

Elle jeta contre elle un cri : un cri de damnation !

La femme ainsi maltraitée fut changée en cadavre

Et le cadavre suspendu à un clou !

Mon corps, en cadavre déshabité

N’est plus que vacuité.

Le clou est le croc du labour

Qui pénètre ma terre en sa Source d’Amour.

Dans mon obscure profondeur,

L’écoulement sanglant est une liqueur de douceur

Répandant sa semence

En ma terre de clémence.

A l’instant où je meurs,

Voilà donc que j’épouse le Grand Taureau fécondateur !

Un échange subtil

Vient de s’opérer

En ma terre fertile.

Je me sens unifiée…

Cependant…

Trois jours et trois nuits – ou peut-être trois mois, je ne sais –

Me seront nécessaires

Pour vivre mes Mystères

Selon le processus sacré de pourrissement…

Le Mariage Sacré

Chaque année, dans ma cité d’Uruk, on célèbre le Mariage Sacré. Il s’agit d’un rituel de fécondité par lequel la Grande Prêtresse, ma divine représentante, va s’unir au Roi, le « taureau fécondant ». Par cet acte, il s’agit d’assurer à la cité, abondance et prospérité, tout en donnant au souverain sa légitimité pour une année. Après quoi, le Roi sera sacrifié pour la communauté. N’ayez crainte ! Il s’agit là d’une métaphore pour dire que le blé dont la graine est enfouie, devra être coupé lorsqu’il sera levé.

Pour l’instant, je veux vous raconter comment mon histoire est jouée, chanté et même dansée,

afin que la hiérogamie – ainsi désigne-t-on l’union d’un humain et d’une divinité – puisse être accomplie dans une divine chorégraphie.

Nous sommes au Printemps, le jour du Nouvel An. C’est le temps des semailles et de l’allégresse, celui d’une nouvelle jeunesse. Mon sanctuaire est en fête. En son centre, on a dressé deux trônes et une Couche Sacrée. Sur cette dernière, des brassées de joncs frais ont été disposées, recouvertes d’un couvre-lit en lin, spécialement confectionné. Au sol, des copeaux de cèdre, parsemés ça et là pour exalter les sens et percevoir l’essence de toute chose, répandent dans l’atmosphère leur subtile fragrance.

Je suis prête.Incarnée dans le corps de ma Première Prêtresse, on vient de me baigner, me parfumer, me parer. J’attends le Roi, dans le rôle de mon amant Dumuzi. Le voici justement qui arrive. Il porte ses rituels atours avec, sur sa tête, la perruque couronnée. Ses bras sont chargés de cadeaux qu’il dépose à mes pieds. Je suis séduite. Nous prenons place sur les trônes pendant que, selon la liturgie établie, l’assistance entonne des chants d’amour dans un refrain scandé. L’époque est sans tabou et les mots sont directs :

O mon Amant, cher à mon cœur,

Le plaisir que tu donnes est doux comme le miel !

O mon Lion cher à mon cœur,

Le plaisir que tu me donnes est doux comme le miel !

De plus en plus puissantes, les voix s’élèvent vers les cieux, tirant de leur transport des accents « mêle-aux-dieux ». Les lyres et les flûtes se mettent à jouer invitant les prêtresses à danser pour les dieux. Alors le Serpent, transparaissant dans leur corps ondulant, s’enroule et se déroule jouant avec leur voile qui vole et les dévoile. Du ciel à la terre et de la terre au ciel circule l’onde d’amour. Le moment est intense. Transportée par la cadence, l’assistance bascule dans une « transe-en-danse ». Je me sens enfiévrée. J’entraine le Roi vers la Couche Sacrée pendant que le chœur continue à chanter :

«Epoux laisse moi te caresser. Mes caresses sont plus douces que le miel.

Dans la chambre nuptiale, laisse-nous jouir de ta beauté généreuse.

« Déesse, j’accomplirai pour toi les rites qui me confèrent la royauté.

Je suivrai pour toi le modèle divin ».

Alors l’invitation se fait plus claire et plus directe :

« Viens labourer ma vulve, homme de mon cœur » !

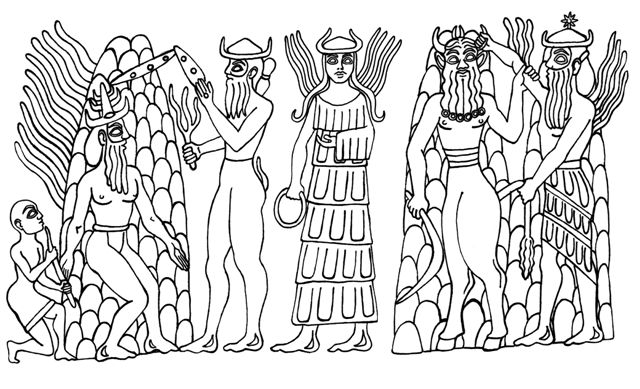

Amoureux sumériens

Bientôt en grand émoi, j’attire le Roi vers moi. Au cours de mille caresses, d’ivresse et d’allégresse ma vulve est labourée et la graine déposée. Mon corps-terre est comblé et mon âme, embrasée. La végétation va pouvoir pousser.

Je souhaite à mon Roi-Dumuzi belle souveraineté et longue vie et lui remets les royaux insignes, l’anneau et la baguette, comme gage de l’union du féminin et du masculin, et aussi bien sûr sa couronne et son sceptre. Par ce geste, je l’investis dans son viril pouvoir et le consacre Roi de statut divin. Qui donc sait encore que la monarchie « de droit divin » provient de ce rituel ancien ?

Cette joie que j’apporte n’est pas que pour le Roi.Tout le monde y a droit. Ainsi, j’envoie ma fidèle servante chercher les hommes aux champs. Ils entonnent mes chants et viennent ensemble jusqu’à mon temple, ce lieu sacré où des Prêtresses d’Amour qui leurs sont réservées vont les aimer activant dans le cœur de ces fiers laboureurs, l’étincelle qui jaillit dans le ciel lorsque s’unissent les corps et dont l’éclat perdure dans l’abondance de leur future récolte. Ces Prêtresses d’Amour, si dévouées à mon culte, vos historiens les ont, moins joliment, nommées « prostituées sacrées ».

De mes chants liturgiques, je n’ai livré qu’une parcelle mais le « Cantique des Cantiques » les reprend, en plus édulcorés..Ah, si mon présent récit pouvait réveiller la vivante expérience de l’Amour humain transcendée par l’Amour divin !

Inanna, Goddess of "Infinite Variety" by Johanna Stuckey

"The Amazement of the Land [of Sumer],"[1] Inanna was a powerful and assertive goddess whose areas of control and influence included warfare, love/sexuality, and prosperity/fertility. As "Lady Who Ascends into the Heavens," she was the Venus Star. One of her regular epithets was "the maiden," and her usual roles -- little sister and pert daughter, sweetheart, nubile bride, and grief-stricken young widow -- all present her as in late adolescence, permanently poised on the edge of full womanhood, not yet tied down by wifehood. It is no surprise, then, that Inanna was a female who behaved like a male and lived "essentially the same existence as young men," exulting in battle and seeking sexual experiences (Frymer-Kensky 1992:29). In addition, Mesopotamian texts normally refer to her as "the (or a) woman," and, even when they call her "warrior," she is still "the woman" (Stuckey 2001:92).[2]

The great American scholar of Sumer and things Sumerian, Samuel Noah Kramer, described Inanna as "...the ambitious, aggressive and demanding goddess of love ..." (1963:153). In historic times, she certainly was goddess of love and sexuality, but she also held and could bestow the mes, the attributes of civilization.[3] Thus, she ruled over many areas of culture. According to Thorkild Jacobsen, these included "the storehouse" (1976:135), "the rains" (136), "war" (137), "Morning and Evening Stars" (138), and what he calls "harlotry," prostitution (Jacobsen 139). Of Inanna, he says:

In the epics and myths, Inanna is a beautiful, rather willful young aristocrat. We see her as a charming, slightly difficult younger sister [to her Sun God brother], as a grown daughter [of her Moon God father]..., and a worry to her elders.... We see her as a sweetheart, as a happy bride, and as a sorrowing young widow. We see her, in fact, in all the roles a woman may fill except the two which call for maturity and a sense of responsibility. She is never depicted as a wife and helpmate or as a mother.(Jacobsen 1976: 141)[4]

This description of Inanna includes many of her aspects, but all the roles that Jacobsen discusses are ones that attach a woman to males by means of the patriarchal family and so control her sexuality and ability to reproduce. Feminist scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky understands Inanna differently: Inanna was the divine model for a role that was not considered socially desirable. "She represents the non-domesticated woman, and she exemplifies all the fear and attraction that such a woman elicits" (1992: 25). She is a woman who is not tied to the patriarchal family, whose sexuality is not controlled for its ends. In addition, Inanna is the fearsome spirit of "the attraction necessary for all sexual copulation, regardless of its social purpose or value." Nonetheless, despite being the goddess of prostitutes, Inanna was, as goddess Ishara, also "patron of marital sexuality" (47-48).

Whereas Inanna seems to have been the foremost female deity of the male-dominated Sumerian culture, a similar goddess Ishtar was worshipped by Semitic-speaking peoples to the north (Kramer 1983: 115, 123). From early times, Inanna and Ishtar became increasingly identified, until, by the period of Sargon the Great (about 2300 BCE), they were so similar that, in discussing them, scholars usually treat them as one deity -- Inanna-Ishtar. Slowly, Inanna in her "infinite variety" gave way to Ishtar, whose primary functions were love/sexuality and war. Finally, with the first-millennium Assyrians and later, only Ishtar remained. We can still see remnants of Inanna in later Ishtar, but, in her final form, Ishtar seems a very different goddess.

Some argue that the identification of the two goddesses was partly the result of a policy of Sargon the Great, the Semitic-speaking ruler of Agade, biblical Akkad, who had conquered Sumer and most of western Asia (Kramer 1983:117). For a time, he managed to unite the whole of Mesopotamia under his rule (Meador 2000: 41). To help him control "the restless and rebellious populations of the southern Sumerian cities" (Meador 2000: 49), Sargon appointed his accomplished daughter Enheduanna as high priestess and thus spouse of the moon god Nanna, tutelary deity of Ur, one of Sumer's most important cities. For over forty years, she held this priestly office (Meador 2000:6). On the back of the now-famous disc found in the 1920s inside the Nanna complex near the residence of Ur's high priestess, an inscription names Enheduanna as "wife of Nanna, daughter of Sargon" and dedicates the disc to Inanna (Meador 2000:37). As incumbent of an ancient and revered office, Enheduanna wielded great power among the Sumerians (Meador 2000:49). However, she is remembered today primarily as a great poet, indeed as the first poet in history whose name we know. The forty-two poems she wrote to temples throughout the area "spread her influence and her beliefs …" (Meador 2000: 50). Further, her three poems to the goddess Inanna "effectively defined a new hierarchy of the gods" and helped Sargon by identifying Inanna and Ishtar (Meador 2000:51). During the period when the Semitic-speaking Akkadians controlled Mesopotamia (2334-2154 BCE), the melding of Inanna and Ishtar continued (Williams-Forte1983:189).

Inanna's symbols appear on some of the earliest Mesopotamian seals (Adams 1966:12), and she is the first goddess about whom we have written records (Hallo & Van Dijk 1968). However, it is clear that she did not spring into existence with the invention of writing. Throughout Mesopotamia, archaeologists have found a large number of female figurines, dating from as early as the sixth millennium BCE. Some, which may be forerunners of Inanna, display prominent breasts and have their hands under or cupping them, a gesture employed by many later goddesses, among them Inanna. In Symbols of Prehistoric Mesopotamia, Beatrice L. Goff traced Mesopotamian symbols from Neolithic times into the historical period. From her study of various symbols and figurines, she concluded that the main concern of the early Mesopotamians was fertility (1963: 21), later one of Inanna's special interests.

In historic times, the sacred animal of Inanna-Ishtar was the lion, which the goddess usually stood on or otherwise controlled. Often winged, Inanna-Ishtar also had close association with birds, like the thunderbird and especially the owl (Lipinkivi 2004: 140). As queen or lady of the sky, she was the Morning and Evening Stars, the planet Venus, and, as daughter of the moon god, Inanna also had connections to both the crescent and the full moon (Lapinkivi 2004: 60,111). An unmistakable symbol of Inanna-Ishtar was the eight-pointed star or rosette, which signified her identification with the planet Venus (Williams-Forte 1983:187). A significant symbol of Inanna was a pair of standards, usually called gateposts, which appeared very early in the archaeological record (Goff 1963:84). The standards signaled both the presence of the goddess and the entrance to her temple (Williams-Forte 1983:188; Wolkstein & Kramer 1983: 47, 106).

Inanna's paramount city in Mesopotamia was Uruk, one of the world's first urban centers. The oldest preserved temple in Uruk is the sacred precinct of Inanna, the E-anna, the "House of Heaven." There archaeologists found some of the earliest writing on clay tablets (Williams-Forte 1983:174-175). As protector of the city, Inanna was originally its owner (Steinkeller 1996:113). She was also a tutelary deity of a number of other cities, and over time many other goddesses were identified with her. Through the ritual known as "the Sacred Marriage," which I will discuss in the next column, Inanna bestowed power on Uruk's ruler and ensured the fertility and prosperity of the land and its people. The "Sacred Marriage" rite spread from Uruk to other cities in Mesopotamia and became one of the central Mesopotamian rituals for validating a king.

Inanna-Ishtar is far and away the most written-about deity in Mesopotamian texts. To judge from the amount of Inanna material extant, she was very popular, though, of course, the survival of so much about her may be just a matter of chance. One of the major poems focusing on the goddess is "The Descent of Inanna [to the Underworld]," a great work of world literature; I will analyze it in a later column. "The Descent of Ishtar" is also extant. Other compositions in which Inanna is central are "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree," which I will also examine in a later column; "Inanna and the God of Wisdom"; songs and poems relating the Sacred Marriage; and hymns to Inanna by Enheduanna and other poets (Wolkstein & Kramer 1983: 4-110).

Despite scholarly views on her "infinite variety" and contradictory nature, there is no question that the Sumerians saw Inanna as a single deity. So there ought to be one factor that unified her varying roles and functions. They were the power in the storehouse and in the rain; the spirit of battle and warfare; Morning and Evening Stars; the impetus for sex and sexuality, not just of the prostitute but also of the marriage bed; goddess of love; bringer of fertility; perpetual adolescence; and non-domesticated femaleness. The answer is hinted at in at least one of her symbols. Birds soar through the skies, also live on earth, and so cross boundaries -- indeed, birds live in a boundary situation. Inanna-Ishtar is also a boundary crosser -- a woman who behaves like a man. She often cross-dressed and was sometimes presented as an androgyne; further, many of her cult personnel were "transvestites and castrates" (Lipinkivi 2004:159).

All of her various aspects and functions involve transition, boundary crossing, and transformation — food and seed in a storehouse seemingly dead, but alive, poised to become something else; rain which changes infertile to fertile or the opposite. On the battlefield fortunes change, and people die — the ultimate transformation. What more appropriate place for the Lady of Transformation than on a battlefield! Morning and Evening Stars herald change: they appear at the boundaries of dark and light, light and dark. Love, sexuality, and sexual intercourse -- all present important ways for human beings to change. No wonder Inanna-Ishtar is patron goddess of sex, sexuality, and love! Adolescence is a transition time -- a non-domestic woman has no fixed place. Neither does the prostitute. Both are crossers of boundaries.

So Inanna was a sex goddess, a love goddess, a war goddess, but she was much more. Although she was a goddess of "infinite variety," she was not, however, a contradictory deity, but a unified one. What unifies Inanna is change -- transformation and transition. She is the way in and the way out, the door, the gateway. What more appropriate symbol for her than gateposts? Forever an adolescent poised at the threshold of full womanhood, maiden Inanna was the eternal threshold through which everything passed in fulfillment of the cycle that is life.

Notes

- By 3000 BCE, the land of Sumer occupied the southern half of Iraq.

- Since I cannot read Sumerian, Akkadian, or Babylonian, I have to work with translations. However, my training in Ancient Greek, Latin, and Biblical Hebrew has taught me that critical comparison of a number of different translations produces a good understanding of an original text. I also check my understanding with colleagues who do read the original languages. Nonetheless I am responsible for any errors and especially for interpretations.

- The word me is difficult to define. Samuel N. Kramer says that the mes were "a set of rules and regulations assigned to each cosmic entity and cultural phenomenon for the purpose of keeping it operating forever …" (1963:115-116). In the poem "Inanna and the God of Wisdom" (Kramer & Wolkstein 1983:12-27), Inanna persuades the drunken god Enki to give her all the mes, and she takes them to her city Uruk. The poem lists over a hundred of them; they include kingship, heroship, truth, prostitution, various priestly offices, power, scribeship, and the crafts (Kramer 1963:116).

- While Inanna seems rarely to have been motherly, the texts do report her as being mother of some sons (Wolkstein & Kramer 1983:70). She also had maternal feelings, especially for the people of Sumer (Lapinkivi 2004:125-127).

Venus, Mary Magdalene, and the Re-emerging Sacred Feminine by Emily Trinkaus

Venus, Mary Magdalene, and the Re-emerging Sacred Feminine

by Emily TRINKAUS

In 2011, I set out on a quest to get to know the Goddess, and my starting point was Venus. My natal Venus is at 10° Libra, in the crosshairs of the Uranus–Pluto square that was just beginning to heat up. I felt a life-or-death intensity about uncovering and reclaiming the Sacred Feminine, in my own life and in the life of the collective. I knew what the shadow feminine looked like: obsession with appearance and an unattainable standard of beauty; codependence and romance addiction; eating disorders and "stuff" disorders (hoarding, hyper-consumption). But I didn't have a reference point for an empowered and liberated feminine. As Marion Woodman has said, "[T]he feminine is so difficult … to talk about … because so few people have experienced it." 1

Very early in my Venus project, Mary Magdalene appeared, totally unexpected and uninvited. I wasn't raised in the Church and had no particular interest in Christianity, so my initial reaction was, "What's Mary Magdalene got to do with it?" But once I delved into her story, I got it. For the past 2,000 years, during the Age of Pisces, Christianity has been the dominant paradigm in the West, and we're all steeped in a belief system that has distorted and diminished the feminine. I could see that getting back to the roots of the closing Piscean Age, revealing and transforming the story of Christianity's "hidden Goddess," was essential to my project. But I was surprised to find numerous explicit links between Venus and Mary Magdalene. This article explores some of those findings and what they might mean for restoring the Sacred Feminine.

Healing the Piscean Paradigm

As we move out of the Age of Pisces, which began around the time of the birth of Christ, the distortions and shadows of the closing age are being brought to light, ripe for healing. Opinions about when one age ends and the next begins vary widely — some say we're already in the Age of Aquarius, and some believe we won't get there for another few centuries. More than the exact time of the shift, what seems important is the recognition that we're in the transition — a time of heightened chaos and turmoil as one paradigm dies and the new one is born.

The symbol for Pisces is two fish swimming in opposite directions but bound together, representing physical reality and the invisible, matter and energy, body and spirit. Pisces is the divine paradox: We are both of this world and not of this world, infinite consciousness yet, while embodied, bound by the limits of space and time. As the last sign of the zodiac, Pisces also signifies oneness, unity, and wholeness. At the end of the cycle, everything dissolves back into the ocean of consciousness, returning to Source.

Early Christianity was made up of a wide range of sects, teachings, and practices, and the Roman Empire's initial response to the new religion was persecution. But that changed in 313 C.E., when the emperor Constantine adopted Christianity as the state religion. By 325 C.E., Rome had codified one "official" version of Christianity, 2 — one that served the interests of the Empire. Orthodox Christianity has enforced the shadow Piscean belief that spirit and matter are separate, exalting the former and demonizing the latter. Spirit is masculine, while the "lowly" body/matter is feminine. God is outside of us. Heaven is where we go once we're done suffering on Earth. Sex is a sin, so we're all doomed from the start. And if we want to bridge spirit and matter, to commune with the Divine, we need an outside mediator, a (male) priest or minister.

As we transition out of the Piscean Age, the old paradigms are crumbling and the Church is in crisis. Sex-abuse scandals — long kept secret by the Vatican — are now erupting into the mainstream. Rather than being a perverse anomaly, it turns out that a shocking number of child sexual abuse cases have been reported, and covered up by Church authorities, for hundreds of years. 3 The rejection of the body/matter, of sexuality, of the feminine, as shameful and sinful has a high price, paid most dearly by children and women.

Mary Magdalene's Rebirth

Reflecting the changing Piscean paradigm and the culture's hunger for the return of the Divine Feminine, Mary Magdalene is making a dramatic comeback. For the past 2,000 years, she's been cast in the role of whore, in contrast to the virgin, played by her counterpart Mother Mary. But the truth is that there's no description of Mary Magdalene as a prostitute in the scriptures. In fact, she wasn't assigned this role until 591 C.E.4 The portrait of Mary Magdalene as a "recovering sinner," writes biblical scholar Cynthia Bourgeault, is "almost entirely a concoction of patristic and medieval Western piety (interlaced with some not-so-pious political agendas)." 5 Even the Vatican admitted its error and revoked her designation as prostitute in 1969, but no one seems to have gotten the memo, and her image as the penitent whore persists.6

Just as a majority of Christians are unaware of Mary Magdalene's declassification as a whore, most are also ignorant of alternative Christian gospels: the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, discovered in 1896, and the Nag Hammadi Gnostic Gospels, discovered in 1945. In these versions of Christ's life and teachings, the "hidden" Goddess is not so hidden. Women play a much more central role and are respected as equals, while Mary Magdalene appears as Christ's best-loved disciple, "the Apostle of Apostles." Bourgeault explains: "Mary Magdalene is seen as 'first among the apostles'… because she gets the message. Of all the disciples, she is the only one who fully understands what Jesus is teaching and can reproduce it in her own life." She is also revealed to be Christ's intimate companion, with strong suggestions of an erotic component to their relationship. 7

Dan Brown's wildly popular The Da Vinci Code — first as a best-selling novel (2003) and then as a Hollywood movie (2006) — challenged orthodox Christianity with an alternative view of Mary Magdalene. The Da Vinci Code puts forth the idea that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were husband and wife, and that the "Holy Grail" is not some special cup or chalice but the sacred bloodline descending from their offspring. However, the suppression and distortion of Mary Magdalene's identity in the New Testament gospels suggest that her role was more radical and less socially acceptable than simply being Jesus' wife. According to researcher Lynn Picknett, "the single most important piece of evidence for their not being married is one of glaring omission: simply, there is no mention of a 'Miriam, wife of the Savior' or 'Mary, Christ's spouse' in either the New Testament or any of the known Gnostic writings." 8

Mary the Light-Bringer

The explicit links between Mary Magdalene and Venus perhaps point to Mary's true identity. In the south of France, where Mary Magdalene landed and established her ministry after the crucifixion, she was known as "Mary Lucifera" or "Mary the Light-bringer." 9 Lucifer is now popularly associated with the devil, conflated with the figure of Satan, but to the ancient Romans, Lucifer (Latin for "light-bringer") referred to the Morning Star, aka Venus. Picknett explains: "This was a time-honored tradition: pagan goddesses were known, for example, as 'Diana Lucifera' or 'Isis Lucifer' to signify their power to illumine mind and soul … to open up both body and psyche to the Holy Light." 10

The planet Venus has a long history of association with the Divine Feminine. The oldest written story of the Goddess (as far as we know) is the myth of the Sumerian Inanna, Queen of Heaven, recorded on cuneiform tablets in approximately 2500 B.C.E. Shamanic astrologer Daniel Giamario (among others) has correlated the story of the Sumerian Goddess — her descent to the Underworld and her return — with the astronomical cycle of Venus (her synodic cycle). 11 Every eight years, Venus traces the shape of a five-pointed star or pentagram in the sky, and ancient depictions of the Goddess often include the image of a pentagram, or sometimes an eight-pointed star.

Another intriguing link between Venus and Mary Magdalene relates to one of the relics possessed by the Knights Templar, who protected and passed on the "heretical" teachings of Christ. Anthony Harris reveals that, according to Inquisition records, among the objects taken from the Knights Templar were two pieces of a woman's skull, labeled "caput LVIII [58]" (caput is Latin for "head"). 12 According to Picknett and Clive Prince, the Knights were said to worship a "severed head … [that] could make the trees flower and the land fertile," and that "represented … Mary Magdalene in the Christian interpretation."13 Flowering trees and fertile land are the domain of Venus, goddess of fertility.

As there are no other "caputs," numbered one to 57, it's safe to assume that 58 is a code. Harris makes a connection between 58 and the Goddess, in the sense that five and eight add up to 13, the number of lunar cycles (and menstrual cycles) in one year. 14 But what jumped out at me was the connection with Venus — five and eight (and their sum, 13) are numbers sacred to Venus, because her synodic cycle forms a five-pointed star in the sky every eight years.

Harris adds another clue to the mystery of "caput 58," that its inscription also bore the symbol for Virgo, the sign opposite Pisces. During a particular Age, the opposite sign is often distorted or denigrated, serving as the hidden shadow to the dominant archetypes or themes. Virgo is the only sign in the zodiac represented by the single figure of a woman, one holding an ear of corn or sheaf of wheat, and this sign has been associated with the Earth Goddess since ancient Mesopotamia. 15 The glyph for Virgo is said to represent the intestines — the part of the body traditionally ruled by Virgo — but also the ovaries, vagina, and uterus, which are associated with the feminine power to create life.

Although in modern usage "virgin" typically means sexually inexperienced or chaste, to the ancients it meant "whole unto herself," in the sense that the Great Mother created life all on her own. To the earliest humans, creating new life must have seemed like a magical and miraculous superpower, thus projected onto the Goddess, giver of all life. By linking Mary Magdalene with Virgo, those attempting to preserve heretical Christian teachings may have been pointing to her significance as the hidden Goddess to Christ's God.

From Priestess to Prostitute

Virgin also meant a sovereign, unmarried woman, often referring to a priestess dedicated to the Goddess. For thousands of years, Venus in her various guises — Inanna, Astarte, Ashtoreth, Isis — was worshiped in temples staffed by priestesses who, far from our modern interpretation of "virgin," participated in sacred sexuality with members of the community. The priestesses were called venerii and taught venia, sexual practices for connecting with the Divine. The Venusian priestesses, Picknett writes, "gave men ecstatic pleasure that would transcend mere sex: the moment of orgasm was believed to propel them briefly into the presence of the gods, to present them with a transcendent experience of enlightenment." It was mostly women (and some cross-dressing men) who led the sexual rites, because "it was believed that women were naturally enlightened." 16

The Goddess religions that flourished for thousands of years were brutally destroyed by the onslaught of patriarchal cultures, and the Old Testament both describes and advocates for this destruction. Merlin Stone reveals that "Ashtoreth, the despised 'pagan' deity of the Old Testament was … actually Astarte — the Great Goddess, as She was known in Canaan, the Near Eastern Queen of Heaven. Those heathen idol worshipers of the Bible had been praying to a woman god." 17

The story of Adam and Eve's eviction from Eden is a key piece of anti-Goddess propaganda. Eve is a decidedly Venusian character — ancient goddesses were commonly depicted with snakes, symbols of erotic power and spiritual knowledge. The apple is one of Venus's sacred fruits; when you cut it in half horizontally, you see a five-pointed star. Ronnie Gayle Dreyer, in her book on Venus, explains that the Eden allegory "reverses the symbolism contained in the Sumerian legend of Inanna, whose regenerative powers are received from the huluppu (date palm) tree. While Inanna's sexuality promised fecundity of the earth, Eve's 'fruitful' offer resulted in expulsion from Eden and the stripping of her powers." 18

Venus's European evolution followed a similar path. By the time of the ancient Greeks, around 1000 B.C.E., Venus had lost her earlier powers as fertility goddess and regenerator of the life force and became primarily the goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite. 19 Zeus, king of the gods, fearing that Aphrodite's irresistible beauty will cause rivalry and war among the other gods, marries her off to Hephaestus. Aphrodite disregards her marriage vows and has affairs with multiple gods and mortals, thereby stirring up jealousy, rivalry, and female competition (shadow Venus). She's often portrayed as vain and self-serving, interested only in her own erotic satisfaction. In one of her most infamous havoc-wreaking acts, she starts the Trojan War.

In the patriarchal paradigm, female sexuality has become a problem — no longer celebrated, honored, and ritualized as the ultimate creative act, a gift to humanity and to the land, the sacred source of life itself. The Goddess's sexual fulfillment no longer ensures fertility but rather generates suffering and chaos. So, where does female sexuality go? As the shrines of Astarte were rededicated to Aphrodite, she became increasingly known as the patroness of prostitution. 20 The role of the sacredly sexual priestess was transformed into that of the temple harlot. Sexuality in general, and women's sexuality in particular, became taboo, sinful, separate from and at odds with divinity, relegated to red-light districts rather than an integral part of the community.

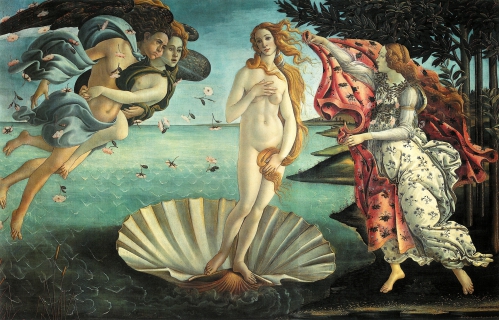

La Victoire de Samothrace, la Vénus de Botticelli et la Vénus de Milo servies sur le même plateau

Mary the Anointer

In the early years of Christianity, there were still remnants of the Goddess religion. One reason we know this is that early Christian patriarchs "denounced the temples 'dedicated to the foul devil who goes by the name of Venus — a school of wickedness for all the votaries of unchasteness.'" 21 To those who were ignorant of the function of the sacredly sexual priestesses, or whose culture and religion opposed their practices, the priestesses would have been seen as ordinary streetwalkers. 22 Mary Magdalene may have been referred to as a prostitute for more than the simple reason of disparaging her character — and this label, though erroneous, may actually point in the direction of truth.

One of Mary Magdalene's key scenes in the canonical gospels is her anointing of Jesus' feet with the precious oil of spikenard. The word "Christ" literally means "the anointed one," but anointing was not a Jewish custom. Rather, anointing with spikenard oil was part of the ancient pagan ritual of the hieros gamos, or sacred marriage. The anointing of the head, feet, and genitals "was part of the ritual preparation for penetration during the rite … in which the priest–king was flooded with the power of the god, while the priestess–queen became possessed by the great goddess." 23

Shortly after his anointing, Jesus is betrayed by Judas, leading to his crucifixion, followed by his resurrection three days later. These events mimic the story of Isis and Osiris, as well as Inanna and Dumuzi, Cybele and Attis, Venus and Adonis, and other myths of the sacred marriage. 24 "In all versions of the sacred marriage, the representative of the goddess, in the form of her priestess, united sexually with the chosen king before his sacrificial death. Three days afterwards the god rose again, and the land was fertile once more." 25 The Gnostic gospels make explicit reference to an initiation known as "the Bridal Chamber." 26 Could it be that Jesus' inner circle of initiates participated in sacred sexuality, and that Mary Magdalene, a priestess trained in the Venusian arts, used her magic to assist Jesus through his death and resurrection transfiguration?

The notion of a sexual Jesus might seem totally far-out to most moderns, whose view of Christianity has been conditioned by centuries of celibate priests. And so much of the history of early Christianity has been deliberately destroyed and distorted (and perhaps hidden in the Vatican basement!) that we may never know the truth of what really happened. But the history of the persecution itself — exactly who and what were targeted by the Church — may shed some light on this issue.

The War on Venus

Rome persecuted "heretics" in isolated cases, from the beginning of Christianity, but it wasn't until the founding of the Inquisition in the 13th century that persecution started operating as a "well-oiled, highly dedicated machine, a conveyor belt for tipping whole communities into Hell." 27 The machine's first victims were the Cathars, a Christian sect in the south of France who held the radical belief that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were lovers — not legally married, but lovers. In fact, Picknett asserts that the Inquisition was "originally set up specifically for the interrogation and execution of the Cathars." 28

What started out as the Vatican's targeted persecution of Christian heretics expanded into an all-out attack on the women of Europe — a "gendercide" that continued through the 18th century and resulted in the deaths of anywhere from 60,000 to one million women (for various reasons, it's hard to get a clear body count). Though some men were also persecuted for witchcraft, the vast majority, more than 90 percent, were women. As Anne Llewellyn Barstow writes in Witchcraze: "Having a female body was the factor most likely to render one vulnerable to being called a witch." And the female body was suspect: "The classic statement from the Malleus Maleficarum [Hammer of Witches], 'all witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable,' summed up the widespread belief that women were by nature oversexed, wicked, and therefore dangerous to men." 29 While sexuality seemed to be the root issue for the Vatican's assault on the Cathars, sexuality was also a significant aspect of the persecution of women that continued for centuries. All phases of the processing of alleged witches were sexualized — from the accusations of witchcraft, which often involved sexual acts with the devil; to the searching and "pricking" of women's bodies (including their genitals) for signs of the "devil's mark" or "devil's teat"; to methods of torture that were explicitly sexual; to the executions themselves, which sometimes included cutting off a woman's breasts before burning her at the stake. (Delving into this chapter of history is not for the faint of heart.) In this war on Venus, a war on the feminine, sexual violence forcefully and effectively severed spirit from body. It became dangerous to be in a body, especially a woman's body.

Why was a sexual relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene so threatening to the Church? And why the full-scale assault on women's sexuality? The ancients knew that sexuality is a powerful and easily accessible avenue to higher consciousness and spiritual power. This is why Venus was the "light-bringer" — through the body, through sexuality, enlightening consciousness. People who are grounded in their bodies and connected with their infinite, divine, spirit selves are not easy to control or manipulate. By turning Jesus into a celibate and by demonizing women's sexuality, the Roman Empire used religion to disempower its subjects.

It was not only the Roman Empire that benefited from suppressing the feminine, but the broader Western project of expanding empire. Barstow points out that the peak years of the European witch hunts, 1560–1760, coincided with Western colonial expansion and the Atlantic slave trade. 30 Cate Montana, in her memoir Unearthing Venus, tells a story that illuminates the connection between colonialism and women's disempowerment. A turning point in her own understanding of the feminine comes when she interviews John Perkins, who lived and studied with the Shuar tribe in the Amazon rainforest. Perkins was told that one of the roles of women — their most important job, on which the survival of the tribe depends — is "telling men when it is time to stop … [M]en hunt animals and cut trees even when there is enough meat and wood, unless women rein them in." 31 Perkins tells of a Shuar shaman coming to visit the United States, asking, "Where are your women? Why are they not telling the men to stop?" 32

Barstow reports that, as a legacy of the witch hunts, European women became afraid to speak up, and protested less: "From having, at the end of the Middle Ages, a reputation for being scolds and shrews, bawdy and aggressive, women began to change into the passive, submissive type that symbolized them by the mid-nineteenth century." 33 The centuries-long war on Venus, which tortured the feminine out of existence and made it dangerous for a woman to speak up or speak out, left industrial civilization free to dominate and exploit the planet and its peoples.

Sacrifice au Dieu Pan

Reimagining and Reviving Venus

Our astrological lens is necessarily colored by our culture, and our view of Venus has been affected by the assault on the feminine. We've projected the more "passive and submissive" view of the feminine onto Venus and the signs she rules — Taurus, Libra, and (in her exaltation) Pisces. For example, Geraldine Thorsten, in God Herself, notes that "traditional astrology … championed Aries as the dynamo of the zodiac, whereas Taurus came off as an amiable dullard at best," but she reveals that, in the earliest zodiacs, Taurus was actually considered the first sign. Thorsten credits Taurus's demotion to the transition to patriarchy: "We're familiar with the patriarchal view through astrological descriptions that equate earth with passivity … Our matriarchal ancestors … had a very different sense of the earth. Not only did they view it as a gift to be shared and cherished, they believed it was a very active quantity." 34

Wanting to bring online this more "active," powerful, and empowering version of Venus, I'm now drawn to pre-Aphrodite goddesses as mythological reference points. Instead of Botticelli's Venus demurely riding to shore on her seashell (which, incidentally, may have been a coded reference to Mary Magdalene), 35 I'm seeing Inanna standing on the backs of two lionesses, as she was often pictured. And rather than viewing Venus as the planet of partnership and marriage, I now see her as representing sacred sexuality. This is essentially the thesis of Demetra George's talk on "Venus, Vesta, and Juno," in which she argues that the asteroid Juno is a more accurate indicator of the marriage partner archetype. By making sexuality the domain of Mars (the masculine), we — and the dominant culture — have ignored or suppressed Venus's ancient roots as the goddess of fertility and eroticism, and the connection between the two: When the Goddess was well-pleased sexually, via her priestesses who embodied the Divine Feminine, then the land would be fertile. 36

Re-wedding sexuality and the sacred, bringing divinity back into the body, making matter "matter" once again by re-infusing it with spirit — these I believe are our main projects here at the end of the Age of Pisces. And I think this is what the links between Venus and Mary Magdalene point to: that as Christianity's hidden Goddess is returned to her rightful place, it's important that she's seen as a sacredly sexual being, rather than simply as Jesus' wife.

Venus's exaltation in Pisces perhaps points to her as a key for healing the Piscean paradigm. My initial association between Venus and Pisces was that Aphrodite was born from the sea. But I discovered an association between Venus and Pisces that predates the Greek myth. The symbol for Pisces is said to come from the Vesica Piscis (literally, "the bladder of a fish"), an ancient geometrical figure consisting of two overlapping circles, where the perimeter of each circle intersects with the other's center. The Vesica Pisces has been associated with the Goddess for thousands of years, and more specifically, with the feminine power of giving birth — the almond-shaped figure formed by the overlapping circles symbolizes the vagina. 37

Researcher Derek Murphy explains: "In the mysteries of Ephesus, the Goddess wore this symbol [Vesica Pisces] over her genital region, and in the Osiris story, the lost penis was swallowed by a fish which represented the vulva of Isis. Likewise, in many examples of Christian art, Jesus Christ is proceeding from this symbol, representing his birth from the Goddess."38 Murphy goes on to show how the Christian fish symbol actually comes from the Vesica Pisces — which you can see in the center shape, plus the lines of the tail.

Now, when I see the Christian fish symbol on the back of a car, I think, "Mary's vulva," and I imagine a religious paradigm that honors a woman's body as sacred, that considers every birth a "divine birth," as if the ability to create life were a miracle, as if life itself were a miracle. I imagine restoring — re-storying — Mary Magdalene to her role as Christ's spiritual equal, and their Sacred Marriage as essential for opening his "body and psyche to the Holy Light," in the tradition of the ancient Venusian priestesses.

Déesse et planète

References and Notes:

1. See: www.feminist.com/resources/artspeech/genwom/conscious.html, "Conscious Femininity," keynote speech for the 2004 Women & Power Conference by Marion Woodman (accessed December 2014).

2. Cynthia Bourgeault, The Meaning of Mary Magdalene: Discovering the Woman at the Heart of Christianity, Shambhala, 2010, p. 30.

3. See the 2012 documentary Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God.

4. Lynn Picknett, Mary Magdalene: Christianity's Hidden Goddess, Magpie Books, 2003, p. 47.

5. Bourgeault, The Meaning of Mary Magdalene, p. 4.

6. Picknett, Mary Magdalene, p. 48.

7. Bourgeault, The Meaning of Mary Magdalene, p. 41.

8. Lynn Picknett, The Secret History of Lucifer: The Ancient Path to Knowledge and the Real Da Vinci Code, Carroll & Graf, 2005, p. 84.

9. Picknett, Mary Magdalene, p. 95.

10. Picknett's The Secret History of Lucifer, which followed her book on Mary Magdalene, seeks to undo this conflation of Lucifer and Satan. See p. xiii.

11. Daniel Giamario, "The Synodic Cycles of Venus," a talk at the United Astrology Conference, 2012.

12. Anthony Harris, The Sacred Virgin and the Holy Whore: The Book that Explodes the Secrets of Religion, Penguin Group, 1998, p. 60.

13. Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince, The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ, Simon & Schuster, 1997, p. 121.

14. Harris, The Sacred Virgin, pp. 60 & 62.

15. See: www.skyscript.co.uk/virgo_myth.html, "Virgo: the Maiden," by Deborah Houlding (accessed December 2014).

16. Picknett, The Secret History of Lucifer, p. 59.

17. Merlin Stone, When God Was a Woman, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976, p. 9.

18. Ronnie Gale Dreyer, Venus: The Evolution of the Goddess and Her Planet, HarperCollins, 1994, p. 63.

19. Demetra George, "Venus, Vesta and Juno: The Erotic, Spiritual and Creative Dimensions in Relationship," a talk for the United Astrology Conference, 1995.

20. Ibid.

21. Picknett, The Secret History of Lucifer, p. 59.

22. Picknett, Mary Magdalene, p. 48.

23. Ibid., p. 58.

24. Picknett, The Secret History of Lucifer, p. 72.

25. Picknett, Mary Magdalene, p. 60.

26. Picknett, The Secret History of Lucifer, p. 65.

27. Ibid., p. 138.

28. Picknett, Mary Magdalene, pp. 31 & 36.

29. Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, Pandora, 1994, pp. 16, 135–136.

30. Ibid., p. 12.

31. John Perkins, The Secret History of the American Empire: Economic Hit Men, Jackals, and the Truth about Global Corruption, Dutton, 2007, p. 69.

32. Quoted in Cate Montana, Unearthing Venus: My Search for the Woman Within, Watkins Publishing, 2013, p. 7.

33. Barstow, Witchcraze, p. 158.

34. Geraldine Thorsten, God Herself: The Feminine Roots of Astrology, Avon Books, 1980, pp. 3, 5, 27–28.

35. See Kathleen McGowan's novel, The Poet Prince, Simon & Schuster, 2010 (Book III in her series The Magdalene Line).

36. George, "Venus, Vesta and Juno."

37. See Derek Murphy's article at www.holyblasphemy.net/marys-vulva-jesus-christ-vesica-pisces-and-the-christian-fish-symbol/ (accessed December 2014).

38. Ibid.

Brigid

Brigid ![brigid.gif]()

Entends mes prières et mon appel, O Brigid

Toi qui nourris les destins les plus arides

Que ton baume de vie emplisse mon vide

Déesse de fécondité aux multiples reflets

Dans le foyer de chaque celte, tu es aimée et vénérée

Médecins, artisans, poètes ; tous louent tes bienfaits

Née du Feu de la vie, tu mets au monde la triade divine

Ton Feu réchauffe, parfois consume et toujours illumine

Ta présence chante le renouveau et chasse la famine

Tu présides avec générosité à la lactation des brebis

Quand repose paille tressée en croix sur sa couche de pissenlit

Fille du Dagda, épouse de Lugh , sage femme de Marie

Tu es une et multiple, nommée Korridan, Eithne ou Etain

Mère de souveraineté, nul ne t’a jamais prié en vain

Aube de la vie, lait de la Terre, tu nous invites au festin

Entends ma prière chantée au confluent des trois cours d’eau

Rappelle-moi, nu (e) à la source de l’essentiel, sans aucun oripeau

Que ton Feu me purifie afin que mon flux s’écoule dans ton halo

Que ta bienveillance éclaire les contours de mes danses

Que ta blancheur peigne la profondeur de mes transes

Que tes dons jonchent les pas hésitants de ma conscience

Minerva : un exemple de la religiosité romaine

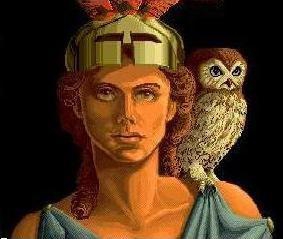

"Je chante d'abord Pallas Athéna, la glorieuse déesse aux yeux pers, dont l'intelligence est vaste et le cœur indomptable, la vierge vénérée qui protège les cités." Hymne homérique |

Minerve fait partie de la triade capitoline (Jupiter, Junon et Minerve) dans le Panthéon romain. Elle est née armée est casquée du crâne de Jupiter. Elle est déesse de la cité, de la sagesse, de la raison et de la guerre stratégique. Elle a inventé le char de guerre et la bride qui permet de dresser les chevaux. Fille aînée et préférée de Jupiter, il lui confie parfois son bouclier et la foudre. Protectrice de la vie civilisée et de l'artisanat, c'est une déesse guerrière, ardente, qui vient souvent en aide aux humains. L'arbre qui lui est consacré est l'olivier, l'animal la chouette. Ainsi nous voyons bien qu’elle est la traduction romaine de ce que fût Athéna Pallas dans le Panthéon grec. Minerve avait décidé de rester vierge, elle refusa toujours de se marier. Une fois, un homme la surprit en train de se baigner. Pour le punir, Minerve le rendit aveugle. Reconnaissant qu'il n'avait finalement eu aucune envie de l'importuner, elle lui donna le don de voir le passé et l'avenir. Ainsi elle est une guerrière puissante capable de veiller sur sa virginité comme sur celle du foyer ou de la cité protégés par elle mais aussi de faire preuve de sagesse et discrimination et devenir de ce fait celle qui guide (invention de la bride pour les chevaux et capacité à lire le passé et l’avenir). Une Déesse guerrière non belliciste donc. Minerve fût aussi la parèdre de Bélisama chez les celtes et ainsi par assimilation et accommodation son culte en Gaule a souvent pris le relai de celui porté aux Déesses Mères gauloises avec des temples qui lui furent dédiés sur de vraisemblables sites cultuels gaulois.

Minerve dans le Languedoc est aussi une cité fortifiée qui aura son heure de gloire et de drame durant la triste croisade contre le catharisme mais aussi un territoire : le minervois. Il est supposé que, sur ce site il y avait un temple et un culte qui était dédié à Minerve, sans doute sous la cathédrale Saint Nazaire ceci expliquant pourquoi ce secteur est encore appelé «Minerva». En effet après que le général Marius écrase Cimbres et Teutons prêt d’Entremont (Aquae-Sixtia puis Aix en Provence) en -120, les romains décident de rester sous le fallacieux prétexte de protéger la cité Phocéenne de Massalia des Saliens et des Voconces. Ainsi naquit la Provincia romaine qui deviendra donc la Provence puis la Narbonnaise. Fort intelligemment, les romains impérialistes empruntent leur divinités aux vaincus, proposent les fertiles terres occitanes à leurs légionnaires vétérans et corrompent l’aristocratie celte mettant ainsi fin à la civilisation des Oppida gaulois pour donner naissance à une ligne de colonies romaines le long de la voie Domitienne, du nom du consul Domitius Ahennobarbus

Ainsi le territoire des Volques Arécomiques a été subdivisé en quatre cités : BAETERRAE (Béziers, colonie romaine), LUTEVA (Lodève, colonie latine), NARBO (Narbonne, colonie romaine) et NEMAUSUS (Nîmes, colonie latine) |

En 46 avant JC, les vétérans de la Xème Légion Césarienne sous la conduite de Tiberius Claudius Nero, père de Tibère, s'installent en Minervois. il fallait les récompenser de leur vaillance au cours des guerres d'Afrique (d'où la plupart des légionnaires ramenèrent des cultes orientaux). les voies romaines sillonnant en tous sens le bassin de la Cesse, nul surprise donc s’ils consacrèrent l’emplacement fortifié qui deviendra la cité de Minerve à une Déesse guerrière aussi prestigieuse par ailleurs protectrice de la famille et du foyer. Dans le même ordre d’idée, le premier habitant de Vendargues (toujours en Languedoc) fut un vétéran de la légion romaine qui aurait reçu des terres sur lesquelles se trouve le village actuel. Ce vétéran se serait appelé Venerianicus, ce qui aurait donné par évolution phonétique le nom actuel du village mais l’on peut aussi retrouver dans le nom du village la racine de la Déesse VénusLa religion était sans conteste le fondement de la cité romaine. « C'est par la religion que nous avons vaincu l'univers », disait Cicéron. Les Romains de plus implorent les dieux non pour les honorer, mais pour se les concilier, non pas pour avoir la force d'obéir à leur volonté, mais pour les plier à leurs désirs. Le sentiment du Sacré était donc omniprésent dans la société romaine tant dans la sphère privée que la sphère publique ; la religion romaine, résolument polythéiste, se composant d’un ensemble complexe de croyances et rituels pour se concilier les faveurs des Dieux. Le lieu de culte romain est désigné par le mot Templum : c’est le lieu où les Augures font leurs observations et la demeure de la statue représentant la divinité ; les cérémonies et rituels ayant lieux en plein air devant le fronton de cette demeure du Dieu ou de la Déesse. On sait que le calendrier républicain ne comptera pas moins de 45 jours de fêtes religieuses.Les pratiques religieuses romaines se retrouvent partout et en tout comme leurs déités

|